Container spot rates have peaked as all major trades see prices fall

There was more evidence in this week’s container port freight markets that peak prices on ...

TFII: SOLID AS USUALMAERSK: WEAKENINGF: FALLING OFF A CLIFFAAPL: 'BOTTLENECK IN MAINLAND CHINA'AAPL: CHINA TRENDSDHL: GROWTH CAPEXR: ANOTHER SOLID DELIVERYMFT: HERE COMES THE FALLDSV: LOOK AT SCHENKER PERFORMANCEUPS: A WAVE OF DOWNGRADES DSV: BARGAIN BINKNX: EARNINGS OUTODFL: RISING AND FALLING AND THEN RISING

TFII: SOLID AS USUALMAERSK: WEAKENINGF: FALLING OFF A CLIFFAAPL: 'BOTTLENECK IN MAINLAND CHINA'AAPL: CHINA TRENDSDHL: GROWTH CAPEXR: ANOTHER SOLID DELIVERYMFT: HERE COMES THE FALLDSV: LOOK AT SCHENKER PERFORMANCEUPS: A WAVE OF DOWNGRADES DSV: BARGAIN BINKNX: EARNINGS OUTODFL: RISING AND FALLING AND THEN RISING

Shipping lines handling Ukrainian cargo are beginning to loosen the terms on which freight can be transported into the country.

They are reducing some of the complications of importing non-military supplies into the country, which has been at war with Russia since 24 February.

Freight costs to and from Ukraine have increased as a result of the war, mainly because shipping lines that can no longer insure cargo or equipment moving into a war zone are demanding hefty deposits for equipment as protection.

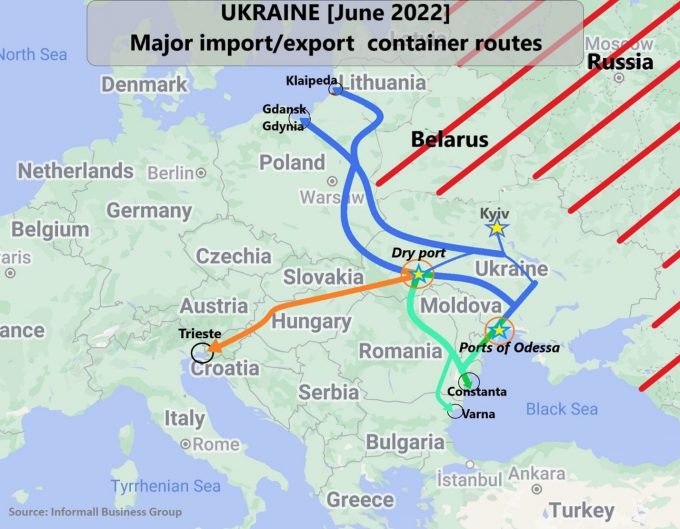

Restrictions on the use of containers has meant that Black Sea ports such as Constanta in Romania and Varna, further south in Bulgaria, and dry ports on Ukraine’s western border have been forced to destuff containers before delivering freight by truck, raising costs and slowing goods transit.

Some freight forwarders are now reporting lines are looking for ways to relax the terms on which freight into Ukraine is delivered with trusted partners.

One source told The Loadstar: “Some regional and international lines have relaxed their requirements for individual forwarders; this is not a policy, but a shift that could make things easier for importers as well as exporters.”

Depending on the type of freight and the relationship the forwarder has with a line, the carrier will demand a deposit of between $3,000 and $6,000 for a container, or up to $8,000 for a reefer box. In addition, carriers may also ask for a letter relieving them of any obligations for freight delivery once the cargo enters Ukraine.

Daniil Melnychenko, of Odessa-based freight consultancy Informall BG, said: “Some shipping lines allow the movement of import containers to Ukraine via rail only, such as ONE and Zim. Others, including MSC, Maersk, OOCL, CMA CGM and Cosco, allow containers to be transported via trucks and rail, however, a deposit is necessary. Empty drop off is allowed only in certain places in Ukraine or, alternatively, empty containers must be returned to the non-Ukrainian port of pick up.”

None of the containers is allowed to head for the front line, only to dry ports and depots mainly in western Ukraine and Odessa, where there is limited or no fighting.

Meanwhile, Informall BG reports, Baltic and Black Sea regional ports are developing new transit corridors.

“Ukrainian cargo needs to be moving under minimum checks and accelerated customs procedures, minimising infrastructure and bureaucratic obstacles on the routes, where possible,” said Informall.

Allowing the free flow of containers would expedite deliveries of essential import goods and humanitarian aid to Ukraine from foreign seaports and decrease freight costs. Additionally, with more freight entering Ukraine, there would be more empty containers for export cargo, which would support the country’s economy.

Even with some lines relaxing their criteria for imports, Informall reports that most carriers remain conservative and continue to follow internal risk-mitigation procedures for inbound equipment.

Vassiliy Vesselovski, CEO of Informall BG, said some lines were looking for alternative solutions to shipping.

“I believe more carriers will offer an intermodal service to Ukraine through the western border in time, primarily via railway connections, along with barge and truck services.”

As the war has unfolded, Ukrainian shippers have paved the way to international markets via container terminals in Poland, at Gdynia and Gdansk, and Lithuania’s port of Klaipeda on Baltic Sea. Black Sea ports at Varna in Bulgaria, Constanta in Romania and, more recently, Italy’s port of Trieste on the Adriatic are offering intermittent services.

All these routes are supplemental to the major Ukrainian import services through the currently overloaded terminal in Constanta, Romania.

“Today, while Ukrainian sea ports remain blocked, cargo is being delivered via complex railway connections and freight trucks in both directions. Freight transport is being delayed at most cross-border points of Ukraine, in both directions, mainly due to multiple bottlenecks on the route,” explained Informall.

According to the consultancy, average waiting times for trucks waiting to cross the border into Ukraine is four to five days, while exports to Constanta can take up to nine days.

On Ukraine’s north-western border with Poland, there are more crossing points, which provide a higher throughput, allowing containerised cargo to and from Gdynia and Gdansk within a more reasonable time.

Daniil Melnychenko, data analyst at Informall, explained: “it took around three-four weeks for Ukrainian shippers and regional transport stakeholders to adapt to the new martial law reality, and start developing alternative routes for containerised cargo. Obviously, those alternatives are much more expensive and less efficient, but when one is committed to continue business during the war, they have no other choice but to take risks and pay the price.”

Meanwhile, the Kyiv government has also trusted the country’s logistics experts and has allocated $7.4m to the ministry of infrastructure from the reserve fund of the state budget to ensure safe navigation in Ukrainian waters and rail transport in the Danube region.

Comment on this article