Are UK businesses ready for safety and security declarations for EU imports?

Alex Pienaar, HM Revenue and Customs’ (HMRC) director of customs policy & strategy, explains what ...

F: MAKING MONEY IN CHINAMAERSK: THE DAY AFTERDHL: NEW DEALGXO: NEW PARTNERSHIPKNIN: MATCHING PREVIOUS LOWSEXPD: VALUE AND LEGAL RISKMAERSK: DOWN SHE GOESVW: PAY CUTFDX: INSIDER BUYXOM: THE PAIN IS FELTUPS: CLOSING DEALSGXO: LOOKING FOR VALUE

F: MAKING MONEY IN CHINAMAERSK: THE DAY AFTERDHL: NEW DEALGXO: NEW PARTNERSHIPKNIN: MATCHING PREVIOUS LOWSEXPD: VALUE AND LEGAL RISKMAERSK: DOWN SHE GOESVW: PAY CUTFDX: INSIDER BUYXOM: THE PAIN IS FELTUPS: CLOSING DEALSGXO: LOOKING FOR VALUE

Freight and logistics is set to be one of the sectors most affected by the forthcoming vote on the UK’s membership of the EU.

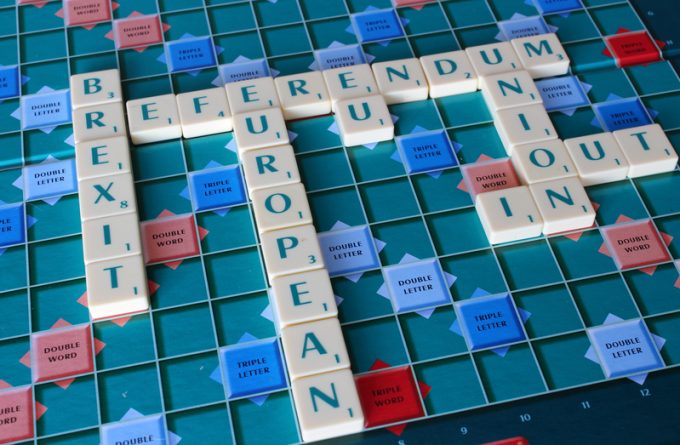

In less than two weeks, UK voters head to the polls to make one of the biggest decisions for a generation or more.

Given the increasingly centrist policies of the Conservative and Labour parties, national elections are routinely little more than a choice of favourite colour, but the EU referendum will likely echo for decades.

Let’s get the (stupid) acronyms out of the way: “Brexit” is a vote to leave; “Bremain” is a vote to remain. It sticks in the craw just to write the words – if this whole process has achieved anything, it is to prove that’s there is no depth too deep at which a pun can be plumbed.

In the interests of honesty, I sincerely hope the country votes to “Bremain”, though I am increasingly nervous it will do the opposite. I grew up in small-town England in the 1970s with obvious European ancestry, and am well acquainted with the entrenched low-level xenophobia. And I see it returning.

That said, it is also safe to say that in the UK’s freight sector, most are on the side of Bremain – the business risk associated with Brexit is simply too high and mooted rewards too uncertain.

In fact, just the process of holding the referendum has already had a deleterious effect on trade at a time when the European economy – of which the UK is currently an integral part – needs all the help it can get.

One senior UK-based forwarding executive told The Loadstar this week: “Europe business had been quite quiet – and it died a death in the last two weeks. It’s not that politics is directly impacting the movement of freight, but long-term deals have been postponed. We have seen two really big contracts put on hold until the outcome of the referendum.”

Given the importance of European trade to so many UK freight firms, the stakes are higher for our particular sector than many others.

Nick Lowe, UK managing director for Dachser, gave me his opinion when I sat down with him at the recent Multimodal show in Birmingham.

“Our business model is predicated on moving large groupage shipments from the UK to Europe in an uninspected manner – it’s all about access to trade.

“What would a Brexit arrangement look like; would we have to fill out customs forms for every shipment, for example?”

Questions abound. David Johnson, managing director of Leeds-based forwarder Tudor International Freight, has rather helpfully outlined three scenarios for the relationship between an “independent” UK and the EU.

Mr Johnson said they could be broadly classified as the Norway, Switzerland and China scenarios, all of which involve time or cost increases when moving goods across newly imposed frontiers.

“Probably the most straightforward and favourable trading model is that adopted by Norway, which, as a member of the European Economic Area (EEA), has a free-trade agreement with the EU.

“A Norway-style arrangement wouldn’t involve UK companies paying duties or taxes when moving goods across borders. However, they would need to produce documents proving where the goods originated, to confirm that they weren’t eligible for duties. This is an increasingly costly task, given the ever-greater complexity of modern supply chains.”

A second scenario would see a series of bilateral trade agreements with the EU, similar to the 120 treaties the EU has with Switzerland, whereby “goods exported from the EU still have to undergo customs clearance and are usually subject to VAT and import duties”.

Lastly, there is the China scenario, which could occur if the UK left the EU after the official two-year withdrawal period without agreeing alternative trading arrangements, and would mean implementing World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules.

“The system would involve us and our former EU partners granting each other access to their markets, and charging the same import duties they levy on other WTO members with which they don’t have free-trade agreements. In our case, these duties currently range up to the 32% levied on wine.

“The 53 free-trade agreements we currently have with other countries as a member of the EU would lapse if we left,” he added.

It is at this juncture in an article when we should turn to statistics, but their use by campaigners on both sides of the debate has created more confusion than clarity, and done more to prove Churchill’s maxim that there are “lies, damned lies and statistics” than anything in living memory.

So, let us instead take a practical example: Tudor currently handles the import of dental uniforms and medical scrubs from Germany for a UK workwear firm.

“If we brought in £50,000-worth under the WTO system, at the UK point of entry we would have to pay £10,000 VAT and approximately £5,000 in import duties on behalf of that company. They would also no longer benefit from being able to delay the VAT and combine it with domestic payments of the tax.”

And, of course, all this is is before the extra administrative costs are added.

Comment on this article